How Soon Will Sports Betting Come to Classical Music?

By Thomas Wolf

Site of Chopin Competition in 2025 (presumably the site in 2045 as well): Philharmonic Hall, Warsaw. (Photo source: Adrian Grycuk, CC BY-SA 3.0 PL, via Wikimedia Commons.)

The year is 2045. The Chopin piano competition has just concluded in Warsaw with a surprise winner.

Of the ten finalists, the betting money, at 4 to 1 odds, was on a 28-year-old male Korean pianist who had sailed through all previous rounds yet failed to pick up a prize in the final round. Instead, the gold medal winner turned out to be a 21-year-old female pianist from Hungary. Odds had projected her at 20 to 1. Any lucky bettor who had risked $1,000 on her to win the top prize before the final round began would have collected $21,000. Had they chosen her to win before the competition began and prior to any rounds being completed, the payout on that $1,000 bet would have been $87,000.

But there were many other opportunities for bettors to win money. A so-called “across-the-board” bet on a pianist to either “win” (1st prize), “place” (2nd prize), or “show” (3rd prize) had a modest payout while a trifecta (picking the top three winners in order) saw a huge return.

Oddsmakers set the performance time of Chopin’s “Black Key” etude at one minute and 46 seconds for pianist #31.

Some bettors went for a different kind of wager. There was the “over/under” bet in which odds makers posted the estimated number of minutes and seconds that it would take a particular pianist to play a specific piece.

In this wager, the bettor could post their estimate for how long it would take for the performer to play the piece and would win if that estimate was closer to the actual elapsed time than the odds makers’ prediction. Then there was the “competition double” (or “competition triple”) in which the bettor had to correctly name a pianist who would successfully pass two (or three) rounds, with the payout rising as things became more competitive in later rounds.

By 2045, betting on the results of piano competitions had become big business and it had greatly enhanced the audience for classical music. Prior to the wagering system, interest in classical music had been overwhelmingly limited to those interested in the art form. But when gambling was added to the mix, others got involved. A new industry grew up around competitions, including for-profit media parsing the likelihood of certain outcomes, offering bios and statistics of participating musicians, and providing profiles of competition judges and their musical predilections.

Musical betting also enhanced the revenue for participating organizations around the world and swelled their audiences. For example, the competition itself received a cut of the betting revenue. So did a concert organization anywhere in the world that registered a certain quantity of wagered dollars. If the revenue produced by that organization exceeded a certain threshold, it won the right to present the winning pianist in the first season’s tour assuming an appropriate touring itinerary could be arranged. A lesser amount would lead to a touring date in the second year, and so on.

For the winning pianist, income earned through the betting pool greatly exceeded the prize money. At least four years of hundred-plus concert dates at high fees (made possible by the presenters’ take from their bettors), ensured a glide path not only to riches but to an established career.

In our apocryphal story, it all seemed too good to be true. What was wrong with this picture?

In a race, the horse that runs the track in the fastest time is the winner. There is nothing comparable in music. (Photo source: Jeff Griffith.)

To begin with, it was based on a false premise. The premise is that a piano competition is like a horse race. The best competitor wins. In a horse race, there is a clear “best”—the horse that runs the track in the fastest time.

In a football game, the team that scores the most points wins and collects the trophy rewarding those that bet on that outcome. If one is looking for the “best” in those particular situations, it can be determined precisely. Similarly, in American football, one can bet on a particular player’s yards gained, or the number of completed passes, or which team will score first. Each of these things can be determined without equivocation.

But that same principle does not apply to music unless one fundamentally misunderstands what defines musical excellence and the role of the performer in attaining it. It is true that one can determine whether a musician plays a piece without making a technical mistake—a wrong note or an incorrect rhythm. But to argue that the one who makes the fewest mistakes is best and should win the top prize has never been the way true greatness in music has been measured. Rather, it is what a performer brings to the work in terms of inspiration and interpretation. And clearly, this is a matter of taste and opinion. Indeed, it is here that music is no longer similar to sports.

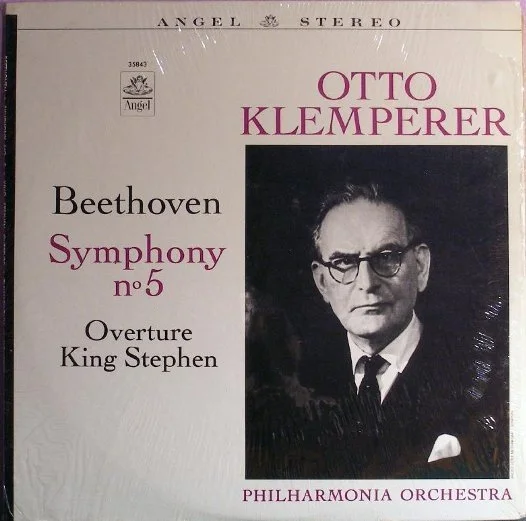

One of Otto Klemperer’s recordings of Beethoven fifth symphony. His tempos are a lot slower than most other conductors but his interpretations are considered sublime. (Photo source: Thomas Wolf personal collection.)

Finally, and unequivocally, there is no single best way to a great performance. Several musicians can play a piece superbly, bringing different sensibilities and interpretations—all equally valid. To choose among them and to determine that one is a winner and the other a loser is anti-musical. What’s more, it fosters a fundamentally flawed understanding on the part of audiences. I cringe when I hear people say, “If I am going to go to a concert and spend money on a ticket, I want to hear the best performer (or ensemble) (or orchestra).” They appear especially happy when that individual or ensemble or orchestra has won a prestigious competition.

Here is a specific example of the problem. Imagine a conductor competition and now think of two of the greatest conductors of the twentieth century as contestants—Otto Klemperer and Arturo Toscanini.

Klemperer’s tempos in, for example, Beethoven’s fifth symphony are quite slow, with one of his recorded performances of the piece lasting 40 minutes. That has many implications for the overall interpretation.

One of Toscanini’s recordings of Beethoven’s fifth symphony. His tempos are far faster than Klemperer’s and those of most other conductors. Again, his interpretations are regarded as awe-inspiring. (Photo source: Thomas Wolf personal collection.)

Toscanini’s tempos are much faster and one of his recordings of the work lasts just over 29 minutes; and again, that influences many aspects of interpretation. Tempo is just one of the many differences between the way these two giants approached Beethoven and other composers. Some might prefer one approach; others might prefer the other. But few knowledgeable music lovers will deny that these were two of the greatest musicians of their time and it would be somewhat silly to argue that one was “better” than the other.

American pianist, Van Cliburn, after winning the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958, became a world- famous superstar. Four years later, he lent his name to another international competition based in San Antonio, Texas. (Photo source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Musical competitions, in part, have helped foster the view that there is one “best” among musicians and incidentally, encouraged a way of playing that is technically close to perfect on the one hand and relatively safe from an interpretative point of view on the other (so as to offend the least number of judges). One can only imagine how many superlative artists of the past would never have won a competition—their idiocentric interpretations and occasional technical mistakes being outside the bounds of “acceptable” competition playing. And for those who compete and do not win, there is a lingering sense that they somehow didn’t make the mark. In a very public way, they were losers even if some will prove to be among the greatest musicians of their generation.

The problems associated with music competitions began in earnest three quarters of a century ago in 1958 when the American pianist, Van Cliburn, won the Tchaikovsky Competition in the Soviet Union.

Poster from the 2025 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, named for the American pianist who triumphed in Russia in 1958, which has become one of the industry’s most prestigious. (Photo source: The Cliburn, issuu.com.)

It was a time of great tension between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.—only one year after the Soviet Union had shocked the world by launching the first satellite (much to the chagrin and feelings of inadequacy on the part of the United States). This same feeling was mirrored by music lovers. No American had ever won the Tchaikovsky competition and the feeling was that in music, as in scientific attainment, the United States was no better than second best. Thus, the political implications of Van Cliburn’s victory electrified his countrymen. He was welcomed to the White House, given a ticker-tape parade in New York (the only classical musician ever to be granted this honor), and seemed in demand everywhere. Between August 11 and September 8, 1958, Billboard reported that his recording of the Tchaikovsky piano concerto had been the number 1 album on the charts for five weeks beating out Johnny Matthis, Pat Boone, Frank Sinatra, and the South Pacific cast album among others. The recording also won that year’s Grammy for best classical performance. Van Cliburn became a wealthy superstar and in one of the great ironies of history, in 1962 he lent his name to another piano competition in Fort Worth, Texas—thus compounding the problem he had helped create. From that day to this, musicians are convinced that one of the quickest routes to fame is to win an influential competition.

And in a way, they are right. In the competitive world of classical music, where making a name for oneself is a challenge, being a competition winner can be a tremendous boost. Presenters wanting to sell tickets have an easier time when their marketing materials can cite competitions won by the artists they are presenting. (I plead guilty to the charge since, for many years, I presented Van Cliburn Competition winners and could anticipate a 25% to 30% increase in my ticket sales.) But for musicians, the staying power of a competition win can be short-lived. A presenter is more likely to be interested in the latest winner. One from twenty years ago may have lost his or her luster.

I acknowledge that it is important to be able to honor great musicians in a very public way but I believe there is a better method for doing so that some prize-giving organizations currently employ. Solicit confidential nominations from a great variety of knowledgeable musicians, convene a jury that meets in secret, makes its decisions in secret, and chooses a musician to receive an award.

In this way, there are no winners and losers—simply an award recipient. Musicians do not compete—in fact, in many cases they are not even aware they are being considered. But even when they are aware and are asked to submit material and concert dates, the jury can decide how it wants to assess and evaluate. The industry still has a mechanism for publicly rewarding talent but the betting scenario with which this blog began is avoided as is much else that is anti-musical.

FOR FURTHER READING

For more on this year’s Chopin Competition, read How to Watch the Olympics of the Piano World and American Wins International Chopin Piano Competition at The New York Times.

On some of the problems with competitions, read Why piano competitions strike a controversial note | The Spectator.

One of the earliest and (to me) one of the best critiques of competitions can be found in Joseph Horowitz’s book, The Ivory Trade: Music and the Business of Music at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, New York: Summit Books, 1990.

In a related piece Opinion | The Quest for Perfection Is Stunting Our Society - The New York Times, Pianist Jonathan Biss discussed why the quest for perfection in music should not be the ultimate goal for a musician.