Did Success Spoil Rock Hunter? – How Musicians Navigate Success

By Thomas Wolf

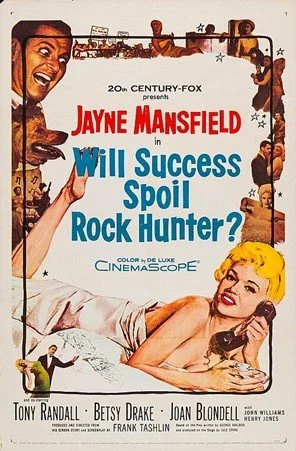

Theatrical release poster for “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?” by Tom Chantrell. The definitive answer to the question in the title is: “It depends how you define success!” (Photo via Wikimedia Commons.)

The title of this month’s blog is taken, in a slightly modified form, from a 1957 zany comedy film. The answer to the question of the movie’s title, “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter,” is an emphatic—it depends how you define success!

What is true for Rock Hunter is true for musicians. Success can come in many forms. And sustaining success, however defined, will depend entirely on the strategies musicians use to prolong long-term accomplishment.

In the film, the protagonist, Rock Hunter, achieves success in the eyes of the world. Elevated from his humble job as an advertising writer to the company’s presidency, he receives all the perks that go along with such a position, including the admiration of scores of young women. Yet he finds himself miserable and ultimately achieves what it turns out he wanted all along… to become a chicken farmer with his one-time fiancée and true love. Success, it seems, is in the eyes of the beholder.

The film lays out the conventional marks of success for a business person and it is a simple matter to come up with comparable measures of success in music. Achieving that success is difficult enough; maintaining it without ruining one’s life, is even harder. The title of a recent article in the Los Angeles Review of Books, “And Then What? The Road After ‘Success’ in the Arts” sums up the dilemma. The minute you are “successful,” the greater the expectations for your continued accomplishments and triumphs and the harder it can be to live up to them. How many carcasses of one-time wonders are strewn in the history of every art form?

For classical music performers, the challenge is particularly acute. Unlike creators, a performer does not have the benefit of a personal product (or several) that persist over time like a symphony or novel or painting. (Recordings don’t count since they can be doctored and are not a reliable guide.[1]) If you have written a great novel or symphony, even centuries later it remains as a testament to what you have achieved and people can return to it again and again. How many performers from those times had comparable enduring success?

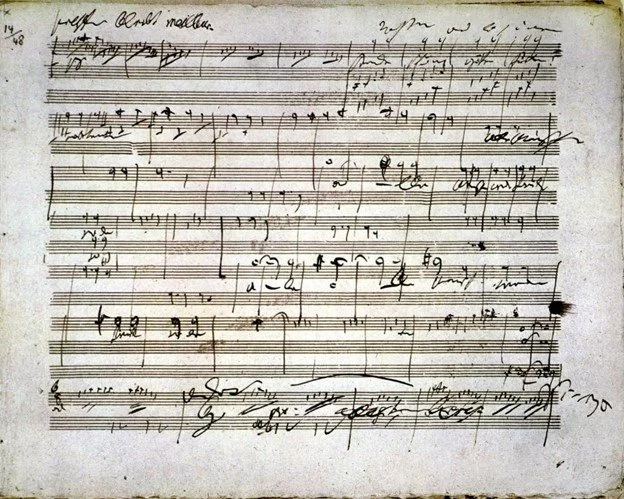

If you were a composer, like Beethoven, who had written a great symphony like his 9th (pictured above), your success would persist over decades, even centuries. But for a performer, what happens on stage is ephemeral and success is fleeting. How many performers from Beethoven’s time can people name?

For the performer, what happens on stage is ephemeral and if your next performance doesn’t meet expectations (and even the best musicians have a few bad nights on occasion), your past successes can be called into question. As a long-time classical music performer put it to me: “No matter how well I have played once upon a time, I am only as good as my last concert. No wonder I get nervous before I go on stage.”

Sustaining high-level success can be exhausting, especially as a performer ages. As with athletes, physical and mental abilities atrophy. Performers must often adapt to changing tastes in repertoire and performance practice. And then there is the problem of critics and audience members who once championed a performer’s success. Decades later, they have disappeared and been replaced by a younger generation who have no idea what might have been true in the past.

Eight Models of Achieving and Maintaining Success as a Classical Music Performer

How have great classical musicians maintained success over a long period and what about those who have tried and failed? Here are some real-world examples.

Success as hard work—Rudolf Serkin

Once someone has achieved great success on the concert circuit, it is immensely difficult to sustain the daily and somewhat exhausting hours of intense practice that got them there. Touring and playing concerts, rehearsing, going to after-concert receptions, and dealing with the press is all so tiring that once a performer has mastered the repertoire that will be performed during a particular season, the temptation is to use what limited practice time one has for brush-up. In the off-season (if there is one), a musician can focus on the works for the following year; but the discipline of scales, arpeggios, and etudes which constituted the practice discipline of one’s early years goes by the wayside.

For the pianist, Rudolf Serkin, there was no substitute for hard work in maintaining his success as a great artist. In fact, it was part and parcel of the definition of success. (Photo source: Wikimedia Commons.)

One musician who bucked this trend and always amazed me was the great pianist, Rudolf Serkin for whom avoidance of serious practice was never an option.

As it happened, I spent much of a particular summer in a room above the studio where Serkin practiced. It was on the campus of the Marlboro Music Festival where Serkin was Director and where he had many time-consuming administrative responsibilities as well as being a regular performer. Nevertheless, he still found time to come every morning to practice. And it was serious, intense practicing as I was able to hear each day. He would spend the first hour of his long sessions playing scales and arpeggios—often very slowly and in various rhythms and dynamics—followed by other exercises. He was often well into a second hour before he moved on to playing some music by J. S. Bach, which was clearly not repertoire he was preparing for performance. When I asked him about it, he said that playing Bach every day was an important way for him to focus musically and something that his cherished colleague, cellist Pablo Casals, did each day as well. Only after that did Serkin begin to practice concert repertoire.

There was something else I found out about him. Unlike many musicians who master the great repertoire once and then basically polish it year after year, he often took time out from his concert schedule to relearn works as, for example, the Beethoven piano sonatas. That way, the performances would always be fresh and would reflect his current thinking about the music.

Rudolf Serkin’s intense work ethic was a key factor in his definition of success and allowed him to sustain it well into his eighties.

For Lea Luboshutz, who came from poverty and experienced persecution and revolution, maintaining success was a necessity. It helped feed and clothe her family. (Luboshutz-Goldovsky-Wolf archive.)

Success as survival—Lea Luboshutz

The violinist, Lea Luboshutz, was from a generation of Russian émigré musicians (mostly Jewish) who lived through pogroms, the Russian revolution, and many forms of discrimination (including, in her case, misogyny and antisemitism). Yet, they prevailed by maintaining their success as concert artists. They had to. Their motivation was fundamental—earning enough income to put food on the table and provide other basic needs for their families.

From the time she was a teen-ager, Luboshutz strived for success. Success brought fame, fame brought patrons and bookings, patronage and bookings brought income, and income brought food and clothing. There was no relaxation to the relentless pace and effort. Success was defined by survival. For a brief time, she could rest on her laurels when a wealthy man supported her and fathered her three children. But after the Russian Revolution of 1917, he died and she was again the sole bread winner for three generations of her family, not only in Russia, but later in Germany, France, and ultimately in the United States. It was only after her daughter married a wealthy man—someone who could provide support for an extended family—that she could relax and redefine success. Her concertizing diminished, she mostly taught, and in time she retired completely at a relatively early age. She did not need the money nor did she need the accolades that motivate many performers. Like the movie hero, Rock Hunter, Luboshutz’s ultimate definition of success was living the good life, especially mentoring children and grandchildren who could carry on the family musical tradition.

Success as versatility and a changed direction[2]—

Pablo Casals, Ruth Laredo

Pable Casals (age 87) backstage at Academy of Music in Philadelphia with my grandmother, Lea Luboshutz. He was there to conduct his oratorio, “El Pessebre.” His new model of success as a conductor and composer came after he had abandoned the intense career as a touring cello soloist for which he had been most famous. (Photo source: Adrian Siegel.)

Pablo Casals: Pablo Casals was considered one of the greatest performing cellists of all time. But as he approached his eighties and even his nineties, the challenges that string players inevitably encounter made it physically difficult to maintain the extraordinary success of a solo career that had characterized his earlier decades. For Casals, this wasn’t a problem because he was able to expand his musical activities to include composing and conducting.

During his late eighties, Casals brought his oratorio, “El Pessebre” to various prestigious concert stages and conducted the performances. During another summer at about that time, I watched him rehearse and ultimately record Mozart symphonies and Bach Brandenburg concertos, demonstrating his conducting prowess as he approached his ninetieth birthday at the Marlboro Music Festival. And one of his last compositions was the “Hymn of the United Nations,” which he conducted in its first performance in a special concert at the United Nations on October 24, 1971, two months before his 95th birthday. As a result of shifting his musical focus, sustaining success turned out to be no problem for this nonagenarian.

Ruth Laredo in 1995 after she went off in a new direction and was able to maintain her success as a solo pianist with her acclaimed “Concerts with Commentary.” (Photo source: Jennifer Laredo Watkins.)

Ruth Laredo: Another musician who I watched change direction and thereby sustain success was the concert pianist, Ruth Laredo. She once told me how difficult it can be for a middle-aged pianist to sustain success in a solo career when there are so many talented young people (including child prodigies) attracting attention. Though she was well-known as a chamber musician, her ability to book prestigious solo engagements became more and more difficult as she aged. Yet she loved the solo repertoire. So when she was 50 years old, she went in a new direction that allowed her to continue her solo playing, albeit in a different format. She began a series of programs at the New York Metropolitan Museum called “Speaking of Music” (later “Concerts with Commentary”) that involved thoughtful talk about music and musicians combined with performance, focusing each time on a different composer. The series was critically acclaimed and was expanded to additional cities. For the next 17 years, Laredo’s success was sustained through this change in direction until shortly before her death. Indeed, this new venture allowed Laredo to continue to perform and succeed as a recitalist, performing the great works of Brahms, Chopin, Dvorak, Faure, Franck, Rachmaninoff, Ravel, Clara and Robert Schumann, Scriabin, Tchaikovsky, and Shostakovich to great acclaim.

Sustaining Success through mentoring—

Gary Graffman, Marcel Moyse, Rosina Llhevinne:

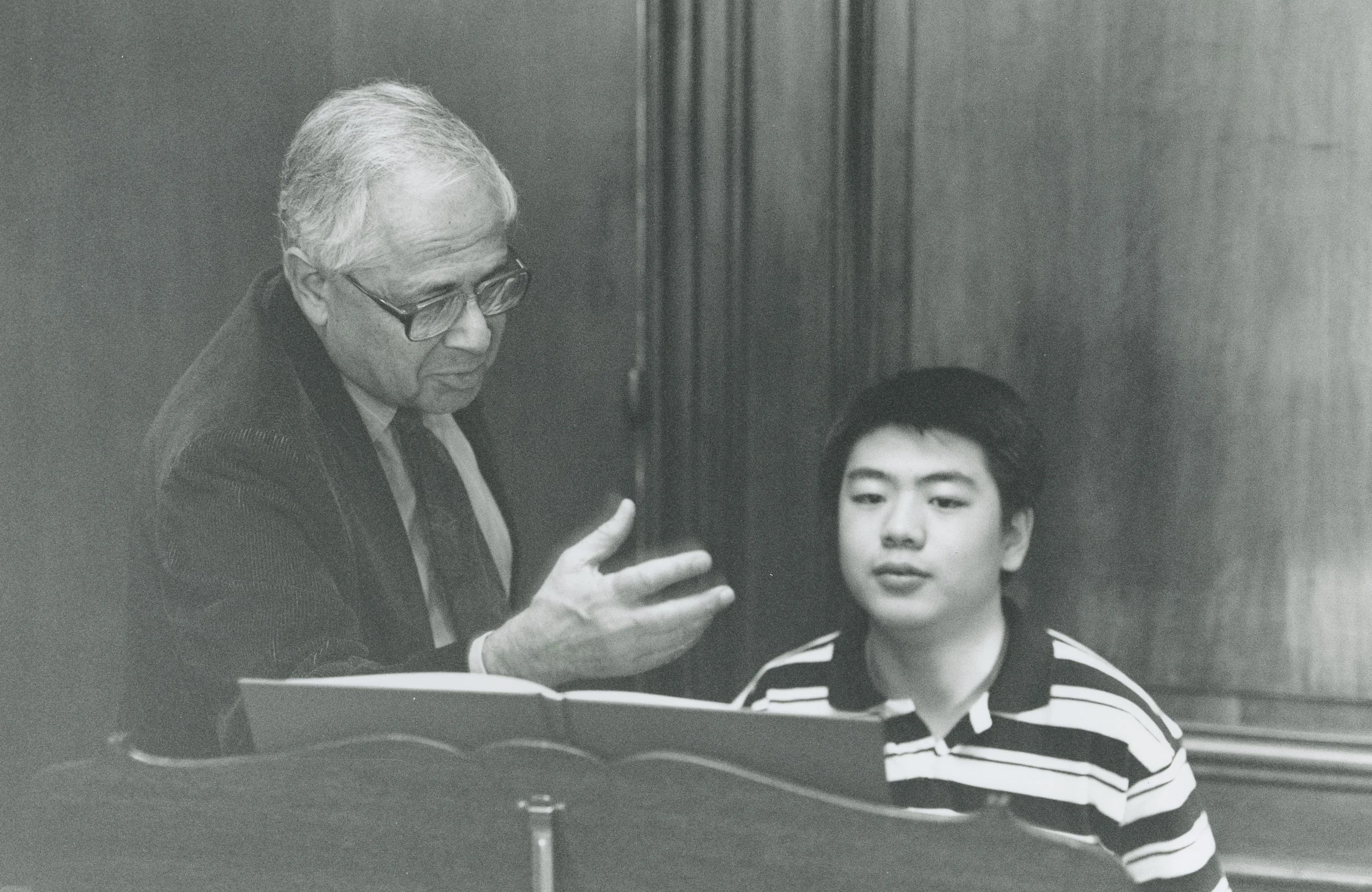

Gary Graffman teaching one of his most famous students, Lang Lang. For decades after suffering a hand injury that essentially ended his concert career, he became one of the most influential teachers in the world. (Photo source: David Swanson courtesy of Curtis Institute of Music archive.)

Gary Graffman: Many successful performers will end up teaching at some point in their careers, and because of their fame, many will attract advanced students. But not all of them will turn out to be successful as great teachers. Those who do can usually boast students who themselves go on to exceptional careers. In some cases, many of these mentors have had their careers as performers interrupted unexpectedly, often for non-musical reasons.

A case in point is the pianist, Gary Graffman, who died recently at the age of 97, still at the top of his game. In his prime, he had little time for teaching because his concert career had him jet-setting around the world. He was considered one of the greatest pianists of his generation. Yet an injury to his right hand essentially ended his concert career (though he did play occasional concerts that included repertoire for the left hand alone). Mostly, however, Graffman shifted his emphasis from performing to teaching and administration, becoming the director of the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music where he turned out many extraordinary students. Indeed, Graffman’s success as a pedagogue is demonstrated dramatically through two of the most important pianists of our own time, Lang Lang and Yuja Wang, who were his students.

Marcel Moyse: Another musician who sustained success by becoming a prestigious teacher was the French flutist, Marcel Moyse. In the 1930s, Moyse was the leading performing flutist in Europe, traveling widely as a soloist and chamber player. He became a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor on the basis of his excellence as a performer, and in 1938, he was invited to America by Serge Koussevitzky to play as part of the Tanglewood Festival. But World War II was unkind to Moyse. He was denounced as a Jew by a jealous rival (he wasn’t Jewish), and was briefly incarcerated before being exonerated. Nevertheless, his reputation was severely tarnished in France and he decided to accept an invitation to relocate to the United States and settle in Vermont where he became a founder of the Marlboro Music Festival.

Flutist Marcel Moyse at a masterclass in Vermont in 1968. After a star-studded career as a performer, he stopped concertizing and became among the most influential flute teacher of his generation. (Photo source: Collection of author.)

Significantly, Moyse did not try to re-establish his career as a performer once the United States became home but began teaching and coaching in earnest. For the next four decades, he became among the most important flute pedagogues in the world, with internationally acclaimed students like soloist James Galway and numerous flutists who took up prominent positions in top orchestras. By the time he died in 1984 at the age of 95, Moyse’s fame and success was as great as it had ever been.

Rosina Llhevinne: In Rosina Llhevinne’s case, the decision to curtail success as a solo pianist was so as not to compete with her husband, Josef, though they played together at times. Even her teaching was limited for many years to preparing advanced students for her husband. But when Josef died, Rosina’s reputation and success as a great teacher blossomed, especially when one of her students, Van Cliburn, won the Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow in 1958. In a somewhat unusual turn of events, in her 70s and 80s, she returned once more to the concert stage, made recordings, and appeared at a memorable performance with the New York Philharmonic at the age of 82. The twists and turns of Llhevinne’s career kept her in the limelight and a success for decades.

Success as force of personality—Isaac Stern

Isaac Stern with his pianist, my brother Andrew Wolf, after Andy contracted an incurable cancer. Stern’s positive energy and optimism probably prolonged my brother’s life. And it was this same force of personality that ensured Stern’s own continued success even after his own playing declined. (Photo source: Luboshutz-Goldovsky-Wolf archive.)

It seems somewhat self-evident that performers will have strong personalities, but few are so extroverted and self-confident that it carries them beyond their waning musical abilities. For many years, my brother, Andrew, played piano around the world for superstar violinist, Isaac Stern. I had an opportunity to watch this musician up close in formal and informal situations. Stern had huge self-confidence in interacting with people and taking action in almost any situation. He would talk expertly (though occasionally erroneously) on any subject. I once drove him from Boston to Hartford. I had been commissioned to undertake a national study of primary and secondary school arts education by the National Endowment for the Arts and had already concluded some of the research. I was astonished by Stern’s enthusiasm for the subject and constant stream of definitive statements. Most were insightful—he was a very intelligent man. Some I knew from my research to be plain wrong. But I was mesmerized as most people were by his articulateness and sense of self-assurance.

Late in his career, Stern was clearly not playing up to his previous level. Orchestra members talked confidentially about how recording sessions often dragged on as musical passages had to be recorded several times to get them right. Critics politely and carefully spoke of deficiencies in his performances. The playing was still energetic and often wonderful but it was not as extraordinary as in earlier years. Nevertheless, Stern continued to be booked at the most important venues internationally. He was extraordinarily popular. People loved that he had opinions about everything and immense energy. This could be turned to great advantage, as with his work almost singlehandedly saving Carnegie Hall in New York from the wrecking ball, or his work on behalf of Israel. Closer to home, I saw his energetic optimism be a crucial factor in extending my brother’s life after Andy contracted an incurable cancer. Stern continued to work with him, prepared him for a concert tour which both suspected would most likely never happen. But Stern’s personality was infectious.

I believe it was this larger-than-life personality that assured Isaac Stern’s continued success until the very end of his own life.

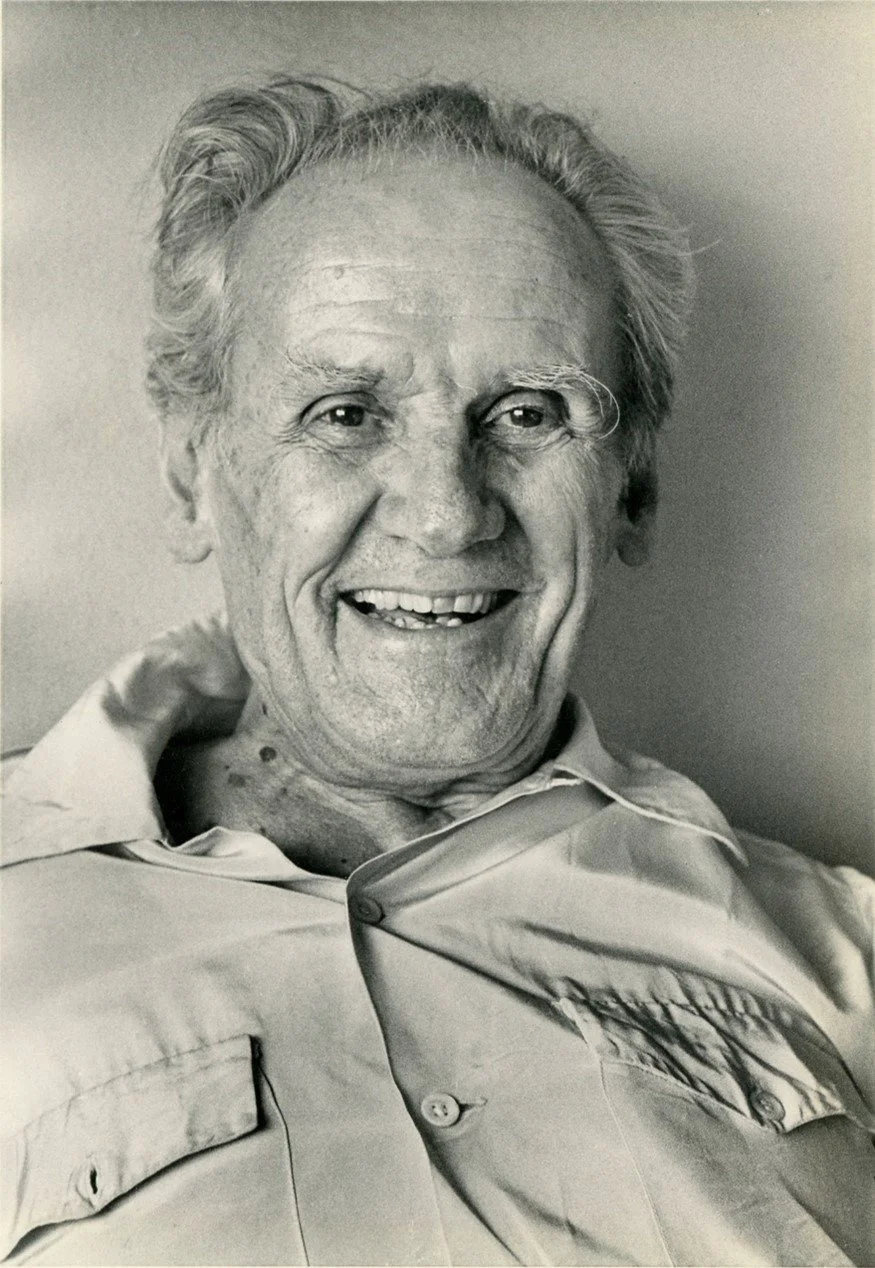

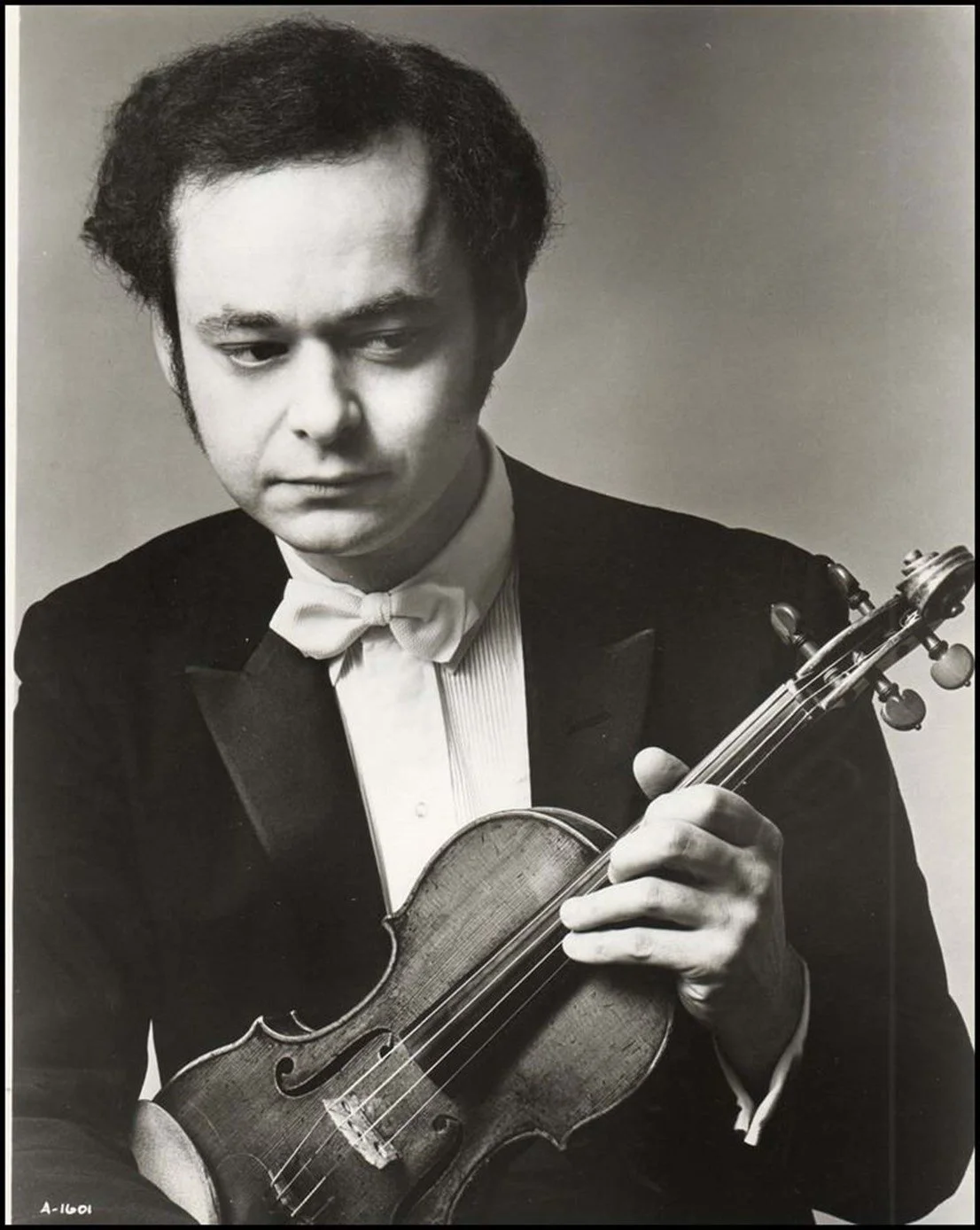

Mischa Elman in 1916. The violinist carried on his father’s tradition of constantly bragging about his accomplishments and belittling his rivals. In many ways, Elman’s need to always be on top fueled a kind of energy to maintain a level of success that other performers simply did not have. (Photo source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Success as being better than the competition—

Mischa Elman

When I was a child, our extended family regularly gathered during December holidays. My parents had a large house and holiday events included sit-down dinners for thirty or forty people. When musician relatives were in attendance, there was music after dinner, but there were also humorous dramatic presentations—take-offs on famous performers. One of my favorites was my uncle Pierre dressed in a tutu representing the famous ballerina, Anna Pavlova, dancing the dying swan with pianist Vladimir Sokoloff playing the familiar Tchaikovsky music on the piano.

Another familiar dramatic scene involved two participants—one portraying my violinist grandmother and the other depicting the famous violinist, Mischa Elman. According to the mise-en-scène, they were in Paris where both had concerts and had just met on the street. My grandmother was talking endlessly about her new summer house in Maine—the views, the number of bedrooms, the porches, and so on. Misha Elman was talking endlessly about all his recent successes—the sold-out houses, the high fees he received, his great reviews, the critics asserting how much better he was than other famous violinists, how bad some of their concerts had been, and so on. The two never stopped talking—neither listening to the other.

From the time Elman was a small boy and prodigy violinist, his father never lost an opportunity to brag about his son and denigrate other violinists who, he claimed, were not as good. It was an obnoxious habit, one that the violinist himself began to emulate as he grew older. It was an industry joke but I believe it was also one of the things that empowered Elman. His need to convince people that he was better than anyone else was an unappealing but energetic contribution to his continued success.

Sustaining success through reliance on stimulants—Michael Rabin

Michael Rabin, a child prodigy whose accomplishments were truly amazing at a very young age. As he aged, and met challenges in sustaining his extraordinary early success, he became dependent on a variety of medications. Complication from these drugs led to a tragic death at the age of 35. (Photo source: Alchetron.)

When child prodigy Michael Rabin made his debut at Carnegie Hall at the age of 13, critics were astonished. Here was a fully developed artist whose effortless technical perfection was matched by profound musicianship. Soon Rabin had prestigious recording contracts and was touring throughout the world. But like so many child prodigies, extraordinary superiority over one’s peers is difficult to sustain.[3] Prodigies encounter a host of problems. Pushed, often by parents to focus exclusively on their instrumental mastery and concertizing, many, like Rabin, never have what might describe as a normal life. Rabin had few friends, in part because he was not permitted to socialize. His relationships with women were awkward and difficult. And, as happens so often in cases such as these, he began to suffer psychologically, he had severe bouts of nervousness, and it began to affect his playing.

Like many musicians, Rabin turned to a variety of medications to address his problems. At first these helped. Taken singly under doctor’s supervision and in moderation, such medicating can aid in sustaining a successful career. But Rabin became increasingly dependent on drugs, turning to a variety of physicians for different medications and often self-administering them in combinations and in dangerous ways. His death at age 35 was at first a mystery—some believed it was suicide—but in the definitive biography of Rabin[4], the details of the death point to complications induced by drugs. Many musicians have seen their careers cut short by dependence on alcohol and other stimulants. Clearly this is a most dangerous strategy for maintaining success.

* * * *

In sum, there are many forms of success in music and even more ways that musicians attempt to sustain it. The greatest musicians have figured out ways to do so. And one of the most important strategies is a simple one: the best musicians know when to quit when continued success becomes unattainable.

[1] There are some exceptions to this statement about recordings given that there have been classical musicians who have maintained success primarily through their recordings. But in most cases, unlike pop, rock, and jazz players, classical performers cannot rely exclusively on their recording output to guarantee continued success.

[2] A recent article in the New York Times profiles opera singer, Marina Viotti, who has made a career out of versatility. As she is still in her 30s, it may be too early to assess how long this approach will assure her long-term career success.

[3] Another article in the New York Times suggests that it is later bloomers that tend to reach the pinnacles of their respective fields, not prodigies, who often flame out.

[4] Anthony Feinstein, Michael Rabin: America’s Virtuoso Violinist, Milwaukee, WI: Amadeus Press, 2005.