Why Do Russians Produce So Many Musical Geniuses But Can’t Seem to Produce a Decent Smartphone?

By Thomas Wolf

The all-male Moscow Patriarchate Choir is an example of the remarkable liturgical singing one can find in Russian churches. (Photo source: singers.com.)

ON A TRIP TO RUSSIA IN in 2015, many things surprised me. I had been prepared for the high level of music-making in concert halls but was struck by the amazing liturgical singing, especially the basso profundo men’s choruses, in the churches that I visited.

As for theatre, I knew Russians loved their native classics like the plays of Chekhov, but I was surprised that certain soliloquies, declaimed by famous actors, were so well known and so popular, that they were often repeated within the ongoing performance of the play. I learned about great Russian painters, largely unknown in the west, and was struck by the quality of the visual art in many museums I had never heard of. Overall, my expectations about the level of the arts in Russia and its appreciation was exceeded by what I saw and heard.

On the other hand, there was something I found rather shocking. Visiting my cousins who live in Moscow and with whom I had communicated electronically for several years, I was surprised to learn that many of their electronics were U.S. brands. Many of them owned late model Apple iPhones. Similarly, their computers were various U.S. brands that I was familiar with at home. Going to their dacha a couple of hours outside of Moscow, we drove through some very fashionable suburbs. On one road I saw high-end car dealerships. The cars for sale were all luxury Western brands: Mercedes, BMW, Lexus, Porche, even Rolls Royce. Not one of those dealerships sold Russian-made cars and the Russian automobiles I did see and ride in did not appear to be up to ordinary Western standards.

Russian Science and Technology

A model of Sputnik I in the Museum of Space and Missile Technology (Saint Petersburg). The launching of this first artificial earth satellite in 1917 proved Russia’s international lead in outer space technical achievement. (Photo source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Over the course of the weeks that I spent in Russia, my impressions were confirmed again and again—incredible arts (much of it the envy of the international community); clunky home-grown consumer technology. I wondered why this was the case. It was not as if Russia had a dearth of great scientists. Its technological achievements had been proven time and time again—indeed, in my own lifetime, the first artificial earth satellite (“Sputnik”) was launched by Russia in 1957 and was able to send signals back to Earth for a full three weeks. The first cosmonaut to journey to outer space and orbit the earth in 1961, Yuri Gagarin, was Russian. Americans were desperate to catch up.

Nor was innovative Russian science and technology limited to post-1917 Soviet times. Consider Alexander Lodygin (1847-1923) whose invention of the incandescent light bulb in 1872 inspired Thomas Edison in the United States to shift his attention to electrical illumination several years later. (Ironically, it is Edison that we credit with the invention.) In addition to Lodygin, it was a Russian, Pavel Yablochkov (1847-1894), who was a pioneer in the illumination of the cities of Europe and more than anyone is responsible for the appellation of Paris as “The City of Light.” Yet their inventions were not taken up in Russia, nor were these brilliant inventors widely celebrated in their own country nor are their achievements widely known today.

A model of the Cherepanov steam locomotive of 1834, a remarkable Russian invention, held in the Sverdlovsk Railway Museum in Russia. (Photo source: Vyacheslav Bukharov, Собственноручное фото licensed through Creative Commons.) Other countries soon surpassed Russia in the development of this invention.

There were many other Russians whose inventions in science and technology were extraordinary. Russian inventors were pioneers in developing steam engines (Polzunov), steam locomotives (the Cherepanovs), the telegraph (Shilling), diesel locomotives (Iurii Lomonosov), the world’s first hyperboloid building [an innovative structure ideal for broadcasting and cooling towers (Shukov)], airplanes (Sikorsky), radio (Popov), the thermal cracking of oil (Schukov), television (Rozing and Zvorykin), lasers Prokhorov and Basov) computer technology (Lebedev), space technology (Tsiolkovsky and Korolev) and heterotransistors (Alferov).[i]

Despite this tremendous history of technological invention, Russia had developed surprisingly few technologies that have been successful among consumers in world markets.

The Dichotomy Between Russian Arts and Science

The late Loren Graham (1933-2024), arguably the foremost American expert on the history of Russian science and technology. His recently published book addresses the seeming dichotomy between the fate of Russian creativity in the arts and in technology. (Photo source: Kurt Peterson.)

All this puzzled me. Here was a country that had produced brilliant artists, musicians, writers, and scientists. So why, for ordinary citizens, was there such a chasm between locally grown arts on the one hand and locally manufactured consumer technology on the other? It would be several years before I came across a satisfactory theory to explain why this was so and it was only in the last year that a new book[ii] by perhaps the foremost American expert on the history of science and technology in Russia and the Soviet Union, the late Loren Graham (1933-2024), provided answers.

As it happened, I knew Graham—he was a Cambridge neighbor associated both with Harvard and MIT, who had advised me as I was writing my own book about Russia. Just before he died and as he approached his ninetieth birthday, he mentioned that he was preparing a book that dealt with both Russian arts and science. He, too, had pondered why Russians had produced such brilliant and famous works in literature, music, and the arts, yet so few innovations that had been embraced internationally in other areas. Why was Russian creativity in fields such as literature and music so strikingly different from the fate of Russian creativity in science and technology?

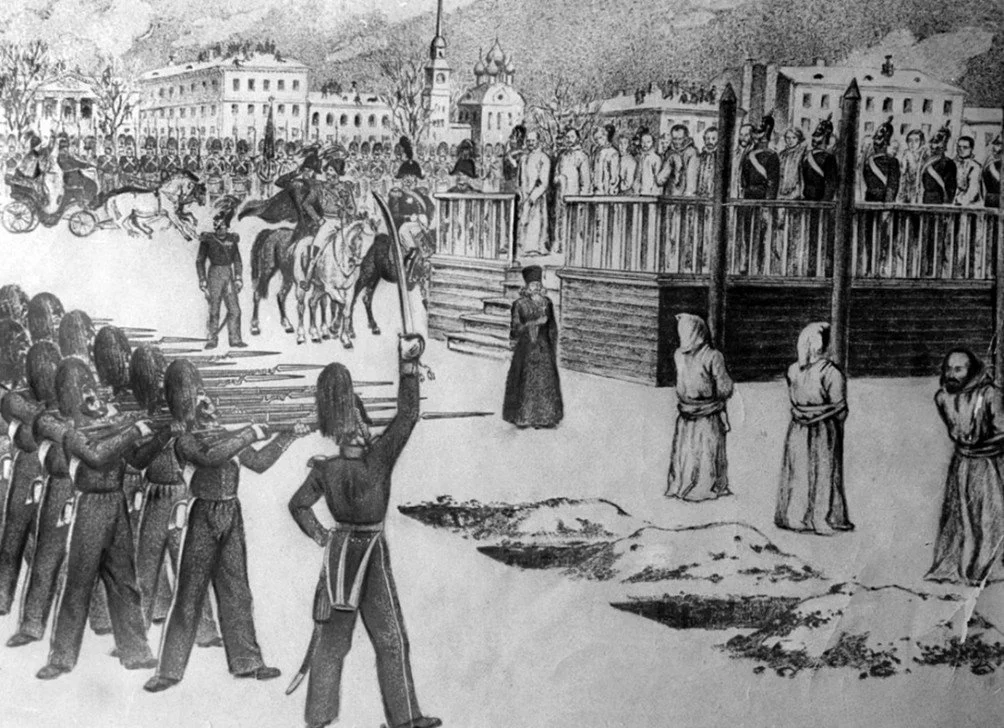

Russian writers were constantly persecuted and their work was often censored, as was the work of various of the country’s composers, yet they still achieved international fame. This drawing 'Semionov-platz Mock Execution Ritual' by B. Pokrovsky features the writer Fyodor Dostoevsky and others before a firing squad immediately prior to their death sentences being commuted and their being sent to Siberia. (Photo source: Wikimedia.)

The Bell Labs building in New York in 1925 at about the time that Oleg Losev, invented and developed transistors and diodes in Russia but lacked the supports to make his invention viable. It would be more than two decades before William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain developed commercially successful transistors at Bell Labs—though most people credit them with the invention. (Photo source: Wikimedia.)

In his book, Graham pointed out that one of the most prevalent theories of why this dichotomy exists is plain wrong. Many people blame it on politics and the long history of Russian and Soviet repression. The problem with this theory is that such repression had been universal in the country—that is, it touched the arts as well as the sciences. According to Graham, “it turns out that some of the most politically repressed authors and composers in Russian history were not only the most creative, but became the best known.”[iii] One can point to Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Solzhenitsyn, Mussorgsky, and Shostakovich among many others whose careers were constantly oppressed by censors and the secret police, yet who became international sensations. Oppression, it turns out, was an equal opportunity hardship in Russia and the Soviet Union, and it was experienced across all creative occupations.

It’s Not Enough to Invent Something

So what is the explanation for why the results of invention in the arts and sciences in Russia are so different? In the arts, writing a great book or a symphony is often sufficient. The creator in many cases does not have to do anything more. In time, when the work sees the light of day and assuming it is truly great, it will ultimately be embraced, even internationally.

In the area of science and technology, however, it is not enough simply to invent something. If you wish it to become a commercially viable product and internationally accepted, the idea itself is not sufficient. There are many important steps that must be achieved and a nation must have various legal, financial, and marketing systems in place to lead a product to widespread acceptance and viability.

An invention comes into the world in an incomplete form. It becomes a widely accepted material construction only with a host of sustaining factors. Some of these include:

A stable research facility, often located within a large corporation, designed for the invention’s development and improvement.

Investors who trade patience with their money for the possibility that their investments will multiply many-fold over time.

Legal protections within a just system of laws including a robust patent system.

A chain of distributors.

Advertising support.

A reliable insurance and credit system.

A risk-tolerant culture experienced with the pay-offs of such a system of supports.

Graham offers the example of the transistor that many believe was invented in 1947 in the U.S. at Bell Laboratories. In truth, a quarter century earlier, it was a lone Russian, Oleg Losev, who developed transistors and diodes in the 1920s. Working alone, without the support of an industrial research laboratory, without investors (since private investors did not exist in Soviet Russia), without advertising (forbidden in the country at the time), and without a patent system that guaranteed a financial return for his invention, he simply was unable to develop and sell the product he had invented.

Technological Innovation & Timing

Another key difference between the arts and technology has to do with timing. In the arts, masterpieces can languish for a long time, but when they appear years or even decades later, they can then receive the approbation and admiration of the world, even after the creators’ deaths. Technological innovation does not enjoy the same luxury of being able to wait. If an inventor misses a time window to turn an idea into a commercially viable product, others will step in and take advantage of market demand.

Dmitri Shostakovich in 1942, four years after writing his first string quartet. Completing fifteen during his lifetime but afraid of persecution by Soviet authorities, many of these masterpieces only became known and popularized after his death in 1975. (Photo source: Wikimedia.)

Consider the field with which I am most familiar—chamber music—and a remarkable series of string quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich. The composer began writing those quartets in 1938 and by 1975 had written fifteen of them.

During much of that time, most of these works were unpublished and were not publicly performed given the level of Soviet persecution of the composer and the fact that these works did not align with Soviet leadership’s musical tastes. Yet, today, decades later, these works of Shostakovich are considered masterpieces and he is probably the most commonly programmed twentieth century composer of string quartets. Widely discovered well after they were written, these quartets’ greatness has only been enhanced with time.

By way of contrast, Alexander Lodygin, the Russian inventor of the light bulb was not so lucky. He did not get the supports he needed and it was Thomas Edison who pounced on his invention and immediately took action to make it a successful product. As Graham put it, “the success of a technology innovator depends on thinking of something new at exactly the right time (to be early or late is to fail), and, even more important, is securing the support of society—in the form of perceived need, investors, credit institutions, customers, legal protection, manufacturing facilities, advertising avenues, insurance possibilities, and distribution networks.”[iv]

Today, Russia continues to be without the systemic supports to encourage market-driven innovation in science and technology. And censorship under Putin is as widespread as it was in Soviet times and earlier. But every once in a while, the censors miss something, only proving that in the arts at least, quality work will find its way.[v]

[i] This list can be found in Loren Graham’s book Fame or Oblivion: Russian Creativity in the Arts and Sciences, published by Cherry Orchard Books (an imprint of Academic Studies Press), 2025, p. 8. Graham and the book will be referred to several more times in this blog.

[ii] ibid.

[iii] Ibid, p. 1.

[iv] Ibid., p. 7.

[v] At a time when the regime is cracking down severely on dissent in Russia, a recent sold-out theatrical production in St. Peterburg is clearly one that censors missed. As described in the New York Times, “everyone expected ’The Kholops,’ a drama exploring oppression, to be shut down soon after it opened in St. Petersburg. Instead, it is two years into a sold-out run.”