If You Want to Be Happy, Don’t Go to that Concert Alone

By Thomas Wolf

We Americans are an unhappy lot. Or so the research says. Despite our great wealth and other positive indicators of well-being, the United States ranks 24th in the 2025 World Happiness Report, behind such unlikely countries as Costa Rica, Slovenia, and the United Arab Emirates. And the trends indicate that things have only gotten worse. In 2022, the U.S. ranked several notches higher at number 16.

There are countless studies that include both formal and informal claims about what contributes to happiness. But the most scientific of them point to an overwhelming and similar finding: positive social relationships are among the strongest predictors of happiness.

As an example recently reviewed by Susan Dominus in The New York Times, Robert Waldinger, a psychiatrist who became the fourth steward of a well-respected Harvard study dating back to 1938, drew on “thousands of questionnaires, saliva samples, genetic analyses, cholesterol reports, dental records, I.Q. tests, wide-ranging interviews and brain scans.

Robert Waldinger, a psychiatrist who became the fourth steward of a well-respected Harvard study dating back to 1938, found that positive relationships are a key to happiness. (Photo credit: Harvard Crimson.)

Much of it added up to one key insight: ‘The clearest message that we get from this 75-year study is this: Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period,’ he said in a TED Talk in 2015. Strong, long-term relationships with spouses, family and friends built on deep trust—not achievement, not fortune or fame—were what predicted well-being. Waldinger had worried that his big reveal was so intuitive that he would be laughed off the stage; instead, the talk is one of TED’s most watched to date, with more than 40 million views.”

This finding is confirmed in the so-called “Global Flourishing Study,” a longitudinal panel study of over 200,000 participants in 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries, spanning all six populated continents. According to its finding, as reported in a May 1, 2025 article by Arthur C. Brooks in The Atlantic, despite negative well-being trends for young people, those who have more friends and intimate social relationships are happier.

One area that some research has focused upon is marriage, which has been closely correlated with happiness in many studies. Today, marriage rates in the U.S. are close to their lowest level since the statistic has been recorded. According to an article by David Brooks, “Fewer people believe that marriage is vitally important. In 2006, 50 percent of young adults said it was very important for a couple to marry if they intended to spend the rest of their lives together. But by 2020, only 29 percent of young adults said that…. Partly as a result of these attitudes, there is less marriage in America today. The marriage rate is close to the lowest level in American history. For example, in 1980, only 6 percent of 40-year-olds had never been married. As of 2021, 25 percent of 40-year-olds have never been married [even though]… there are mountains of evidence to show that intimate relationships, not career, are at the core of life, and that those intimate relationships will have a downstream effect on everything else you do.”

What does all this have to do with concert attendance? I begin with personal history. As a youngster, my parents subscribed to Philadelphia Orchestra concerts. Their subscription translated to a box at the Academy of Music for every Saturday night concert of the season. The box could seat up to six people and was generally fully occupied, often with representatives of three generations of my family and their friends.

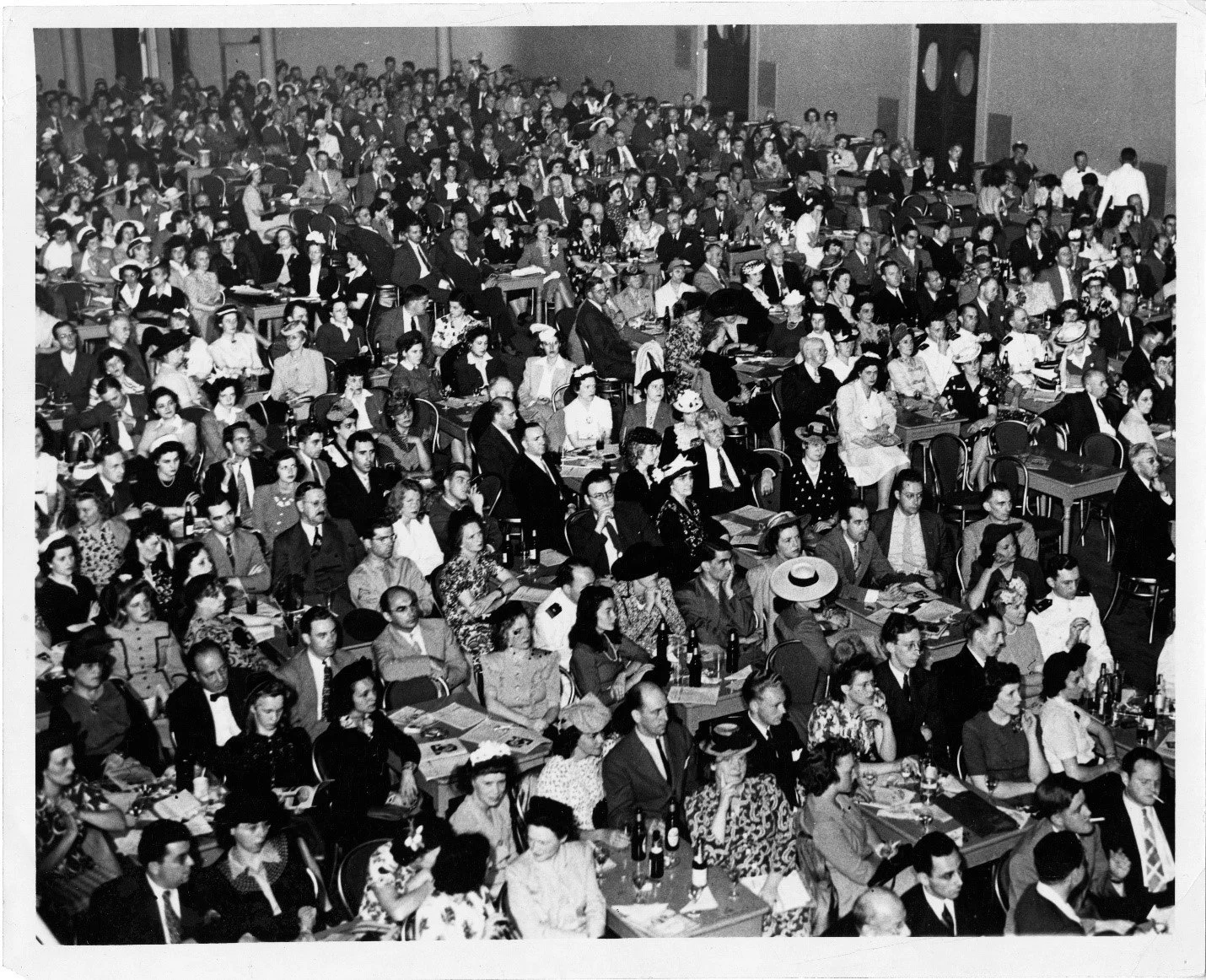

My family occupied one of the boxes just above the ground floor at the Academy of Music every Saturday night at Philadelphia Orchestra concerts when I was growing up. Attendance was always a happy social occasion as well as a musical one.(Photo courtesy Thomas Wolf.)

Attending concerts was a social affair. If all six seats were taken by others as was often the case, my brother and I could go upstairs to the “peanut gallery” for $2 each and sit with musician friends from the Curtis Institute of Music, following musical scores and complaining about the performers as adolescent music students are wont to do. At intermission, I loved going into the foyer where I could meet and greet many others who were regular attenders and acquaintances. Sometimes I ventured back stage where I knew several orchestra members, including two of the flutists with whom I had studied. After the concert, a group of us would invariably go to the local delicatessen for a sandwich and conversation. Even if the music or the performance on any given night was not to my taste, the evenings were always fun. They represent some of my happiest memories.

Many years later when I moved to the Boston area, I began attending Boston Symphony concerts since the BSO had a reputation as being one of the world’s great orchestras. Mostly I would go alone since now I had to pay for tickets and I was still a student. It seemed as if I knew no one there. At intermission, I would search out friends but most of the time I did not recognize anyone. I did know members of the orchestra and thought about going backstage at intermission but the doors to backstage were guarded more vigorously than the gates of a prison. Over time, my attendance dropped off and today I go only occasionally when I can entice a friend or family member.

One way to understand the decline in the social aspect of orchestra attendance is to look at the recent history of the Boston Pops Orchestra. As reported in The New York Times, “For decades after the 1930s, the Pops sold tickets primarily to groups rather than individuals, to the alumni associations and Rotary clubs that helped knit the ensemble into the fabric of community life. Going to the Pops was an inherently social affair; now, though, we bowl alone. [1] Group sales peaked at 90 percent and remained near 80 percent in the 1980s. They accounted for (only) 16 percent of Holiday Pops tickets last year.” Though the Pops remains an important Boston cultural attraction, this represents more than an 80 percent decline in group sales!

A Boston Pops audience in Symphony Hall in 1955 enjoying the concert in groups at tables where refreshments were being served. At one time, fully 90 percent of tickets were sold to groups. Today that figure is less than 20 percent. (Photo Courtesy BSO Archives.)

The data from classical symphony orchestra concert attendance is equally compelling as it relates to the powerful role of social context in driving attendance. The pleasure and happiness derived from going to concerts is clearly related to attending with others. In what may be the largest single study of orchestra audiences, one that included over 25,000 interviews in fifteen different markets, the findings indicate that there is a direct relationship between frequency of attendance at the orchestra’s concerts on the one hand and social context on the other. “Across the 15 orchestras, an average of 85 percent of subscribers have close friends who attend classical concerts, compared to 81 percent of former subscribers and 75 percent of single-ticket buyers. Similarly, 69 percent of subscribers have immediate family members who attend classical concerts, compared to 66 percent of former subscribers and 59 percent of single ticket buyers.”

What happens when two people in a marriage do not have equal interest in going to concerts? One possibility is that attendance will diminish. However, according to the study, “in a ‘taste dissonant’ couple, latent demand can be activated when the positively inclined partner develops a friendship network with shared values around classical music attendance.

The same is true for single people who move to a new area and have difficulty making friends who enjoy going to classical concerts. Often, the desire to attend encourages the single individual to become what the study calls an “initiator,” one who organizes groups to attend. “In some cases, [initiators] are single adults or are in a relationship where the other partner does not share the same cultural interests. Their initiating behavior creates the social context for attendance that is otherwise absent in their lives.”

The Classical Music Consumer Segmentation Study of over 25,000 people is one of the largest ever carried out that examined how people related to classical music. Published in the year 2000, it identified the importance of social context in concert attendance.

According to the study’s authors,[2] “Initiating cultural outings satisfies a deep need to nurture and enrich the lives of their friends and family. For these people, the process of working through the logistics of planning a cultural outing (identifying activities, contacting people, getting the tickets, etc.) is meaningful because it satisfies an emotional need to nurture. The types of groups that initiators get together include:

Groups of co-workers (particularly when the initiator is new to the area),

College alumni groups (went to school together, trying to sustain friendships),

Church friendship groups (shared religious values),

Small family groups (e.g., daughters with widowed mothers and their friends—the initiator wants to “‘be a good son or daughter”),

Friendship groups that are not connected by an external institution like church, employer or family (e.g., girlfriends).

Social context is important to happiness in general but in this specific example, it is linked to the pleasure derived from concert attendance. Unfortunately, we live at a time when the number of significant relationships a typical young person may have is diminishing. According to a recent report, “compared with previous generations of teens, they have fewer friends, spend significantly less time with friends they do have, attend fewer parties, and spend much more time alone.”

The internet clearly has played a role in the diminishment of serious relationships (simply texting one’s friends does not build the kind of sustaining relationships that leads to happiness, according to the research).

Another factor working against forming meaningful relationships is so-called “cocooning”—the desire to live one’s life without leaving home. According to a recent article about Gen Z renters in the Wall Street Journal, young people under 30 are “hunkering down in amenity-rich, high-design rental complexes that offer not just a place to live, but also a self-contained world that creates its own instant community…. Today, some complexes have perks like pools, fitness centers, coworking spaces, social lounges and pet salons. These amenities are efficient… and provide a real world buffer, allowing residents to curate their own mini universes, not unlike personalizing a social-media feed.”

I would argue there is something else that is working against the confidence of the young (and to some extent older people) to build meaningful relationships leading to happiness. We live at a time of social division where it is common and acceptable for one side to demonize the other, where families are riven asunder by political and cultural differences, and where there has been a degradation of public discourse, including abusive personal attacks and offensive language—this, most prominently among our leaders modelling what is presumably acceptable behavior for the rest of us. Forming relationships in such an environment and at such a time can be challenging, carry risks, and for some, simply isn’t worth the effort. One wonders whether the happiness quotient in the United States will continue to decline given this sad reality.

[1] The reference is to Robert Putnam’s classic book from 2000, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, in which he demonstrated, with copious data, that America was transforming from a nation of joiners to a nation of loners.

[2] I am grateful to Alan Brown, one of the principal authors of this study, and a colleague at the consulting firm WolfBrown.