How Can I Enjoy It If I Don’t Understand the Words?

By Thomas Wolf

Who would have thought it? Long after it seemed that the whole debate about opera translations was settled, it has risen its head again. For years, there were credible arguments for singing operas in the language of one’s audience even if it required translating the text of the libretto. Not only would audience members be able to understand what was going on, but singers would be more likely to express proper emotions if they were singing in their own language.

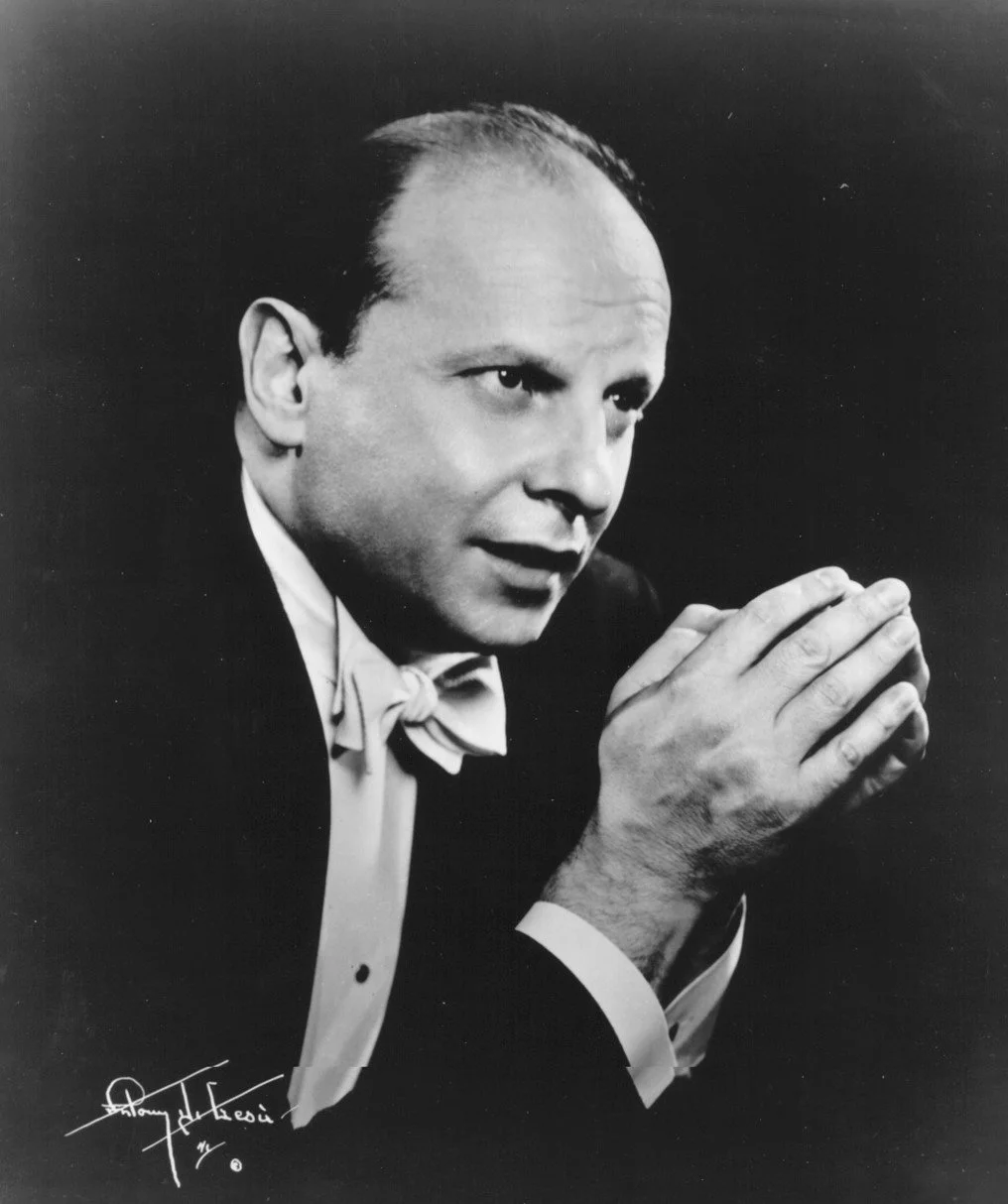

My uncle, the opera impresario, Boris Goldovsky, was a champion of operas translated into English. His various companies used his translations that were matched as closely as possible not only to the words of the original opera but to the dramatic action he wished to convey. (Photo credit: Luboshutz/Goldovsky/Wolf archive.)

Such was the argument advanced by my uncle, Boris Goldovsky, an impresario, conductor, stage director, pedagogue, and lecturer on opera.

Boris was fluent in eight languages and took pride in translating librettos personally. When his various companies toured, they almost always used his translations that were intended not only to match the original language of the opera but also the dramatic action on stage.

Purists scoffed. “How can you abandon the beautiful language associated with the original opera?” they would ask.

Many, if not most, of these people were not fluent in the original language and did not understand it. But in time, they came to love the sounds associated with the original words. Most also did not realize that the tradition of opera translation had been well established in Europe and was common practice for more than a century. This, according to music critic, Anthony Tommasini, who wrote, “Verdi would have found it absurd for a French audience to hear ‘Il Trovatore’ in Italian. Even in Salzburg and Vienna, Mozart’s operas were typically performed in German until World War II.”

Wagner expected his works to be translated into French when they were performed in France. Yet for purists, the idea of singing a famous Italian aria in what many considered the ugly (for singing) English language was an anathema. And during most of the twentieth century, important international opera houses rarely tolerated such a practice.

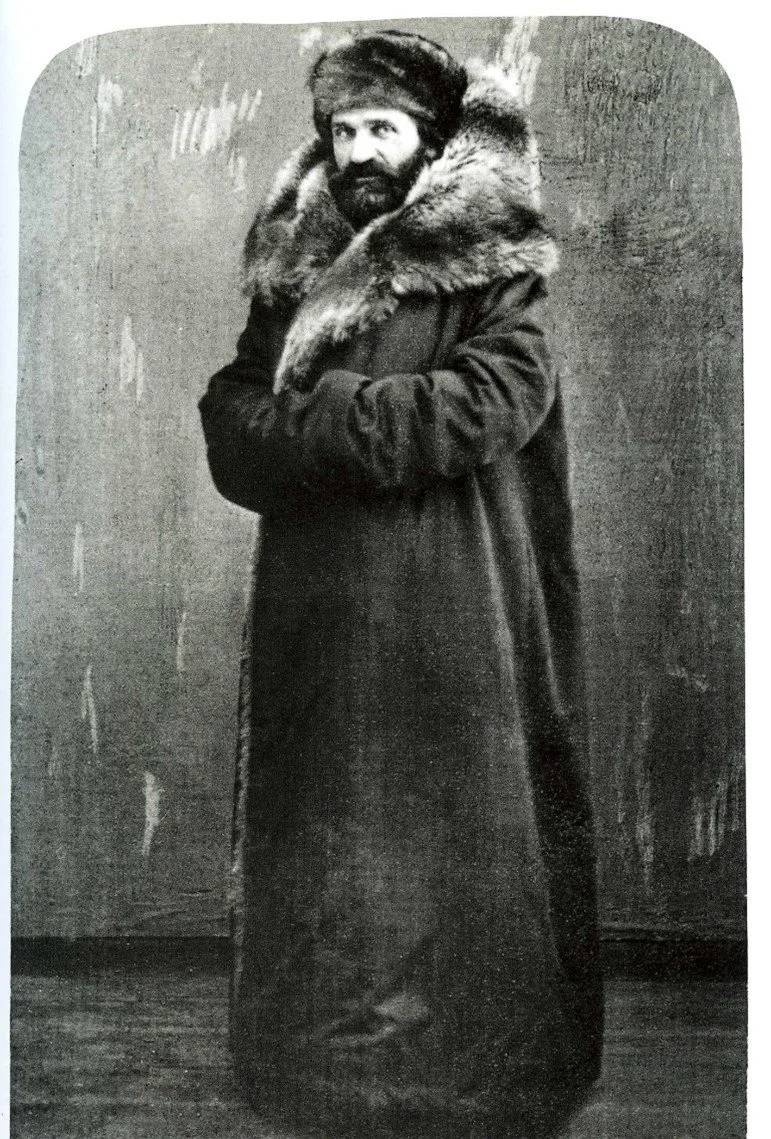

Giuseppi Verdi in Russia in 1861-1862. The great composer expected his operas to be performed in the language of the countries where they were being produced. (Photo credit: Public domain, Wikipedia.)

The two camps were fairly evenly matched for years. But then came supertitles—simultaneous translations in a video feed, most often projected above the stage. You could have your cake and eat it too. You could hear the opera in the original language but view a translation at the same time if you wanted to. Some people, like my uncle, still objected. An audience member, with eyes focused on the translation, would miss much of the dramatic action taking place on the stage. Eyes could not be in two places at the same time. And once one started reading the text, it became habitual.

I realized how right Boris was about this last point. When I attended a performance of “Rosenkavalier” in Prague, I was so used to reading supertitles that I found myself regularly looking up, even though the translation I was viewing was in Czech. I simply could not cure myself of the habit.

In time, the purists won out, especially when supertitles became virtually universal. Opera, for the most part, was sung in the language in which it was written. When the Metropolitan Opera, long an opponent of supertitles, gave way to translations in seat backs that audience members could turn on or off, the game appeared to be won since even this major company found the dual approach of original language and supertitles popular with audiences. The idea of having singers sing in the local language virtually disappeared.

So I was completely surprised to read a May 29, 2025 article in the New York Times by John McWhorter arguing for opera translations.

“The debate over translation in opera is lively and ongoing, but it’s more relevant than ever today, when opera companies struggle to attract new audiences and digital distractions lure away even some devoted fans. Like the qwerty keyboard, sitting through a three-or-more-hour performance in a language we don’t understand is a peculiar cultural phenomenon we accept only because it’s often the only option we’re given. It’s happenstance. And it’s a big part of what keeps opera from reaching more people.”

Except for the reference to “digital distractions” in the quote above, the passage could have been written by my uncle fifty years ago.

I have no idea whether opera companies will once again warm to the idea of opera translated into the local vernacular, but I do know that the art of translation of vocal music is no simple matter. Matching words to notes is complex. And the challenges of translation are compounded when the vocal music is based on a famous work of literature. For those who know the source material, even slight variations can be jarring.

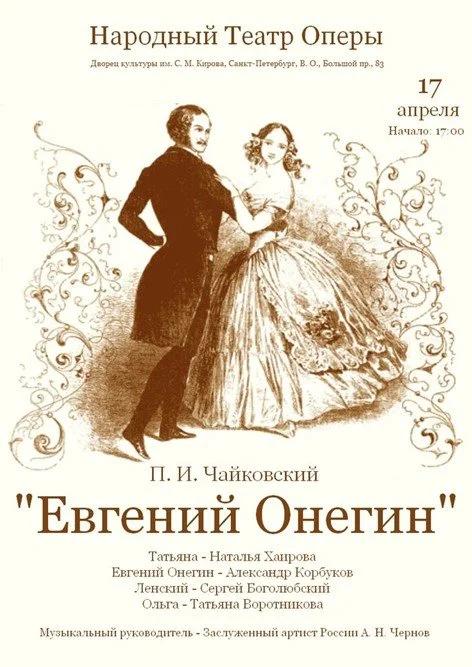

A poster for a Russian performance of “Eugene Onegin,” an opera by Tchaikovsky that my Russian uncle translated into English for a performance in Boston in 1946.

Such was the case when my uncle (who was Russian-born and fluent) translated the text of Tchaikovsky’s opera “Eugene Onegin.” The opera is based on an iconic work of literature—an epic poem by the great Russian writer, Alexander Pushkin. To cultured Russians, the poem has always been sacred—something that is part of Russia’s cultural heritage. Many know long passages both of the opera and Pushkin’s original poem by heart, especially since Russian pedagogy was often based on memorization of important works of literature.

Boris’ task was triply challenging. First, he had to follow the operatic text as closely as possible. But he also needed to take into consideration the original poetic work. If he were to stray in his translation—as is often necessary when setting words to music—he had to toe the line as closely as possible, not only toward the opera libretto but to Pushkin. Finally, the translated words had to adhere to Tchaikovsky’s music, containing the correct number of syllables to match the notes. It did not matter if a Russian word could best be translated by two English words or if two one-syllable words in Russian could best be translated by two three-syllable English words. Such translations would not work with the familiar music that many opera lovers knew by heart. Indeed, experience dictated that the music should always come first in considering appropriate text, even if this meant the translator might have to do some serious word rearranging or some rewriting to make the English words fit Tchaikovsky’s music.

Phyllis Curtin making her operatic debut as Tatiana in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin in a production by the New England Opera Theatre. She sang the work in English in Boris Goldovsky’s translated version.

The first performance of Boris’ translation of “Eugene Onegin” occurred in Boston in 1946. It was produced by my uncle’s company, the New England Opera Theatre. A young American singer, by the name of Phyllis Curtin, was to make her operatic debut as the female lead, Tatiana.

Curtin would go on to have one of the most illustrious careers of any America operatic soprano in the twentieth century. She had studied with Boris both at the New England Conservatory and the Tanglewood Music Center (he headed the opera departments of both at the time). Such was the excitement about her debut and Boris’ translation that my grandmother, the Russian violinist, Lea Luboshutz, traveled to Boston from Philadelphia with my mother to attend. My great Uncle and Aunt, the duo-piano team of Luboshutz & Nemenoff, came from New York to join them. Serge Koussevitzky, Boris’s boss at Tanglewood and the conductor of the Boston Symphony, had another engagement but he was sufficiently interested in the event that he sent his assistant, a cultured Russian lady by the name of Henrietta Leopoldovna Girshman, someone completely familiar with Onegin (both the opera and the poem) to report back. The family and Madame Girshman (known in America by the Anglicized “Hirschman”) were honored with seats in the conductor’s box.

According to my mother’s version of what occurred at the event, there was plenty of chatter among the older Russians during the performance, much to her embarrassment and the chagrin of people around them. Her elders felt free to discuss various aspects of the performance as it was going on, including Boris’ unusual staging of the celebrated “letter scene” when Phyllis Curtin was instructed to sing part of her famous aria lying in bed.

But it was in the final act when things erupted. According to Pushkin’s plot, the hero, Onegin, fresh from his travels abroad, attends a ball. Looking across the room he spies a magnificent woman who resembles the young girl, Tatiana, who Onegin had spurned years earlier. He asks the host, a Prince, who she is and the host answers that it is his wife—indeed, it is Tatiana.

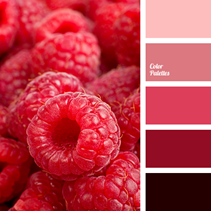

Tatiana’s beret was raspberry-colored according to Pushkin. There is no single word in English to describe the possible color shade that is the equivalent for the Russian word “malinova” making it both awkward to translate and at the same time to fit with Tchaikovsky’s music. (Photo credit: colorpalettes.net.)

In addressing the Prince at this emotion-filled moment, Onegin asks: Who is that woman… “in the raspberry-colored beret.” The original Russian for the phrase in quotes is “в малиновом берете” (transliterated “ve malinovom berete”). The Russian single-word adjective (malinova or raspberry-colored) is derived from the Russian noun малина (malina) meaning raspberry.

Finding that the phrase “raspberry-colored beret” didn’t work, Boris decided to describe Tatiana’s head covering as a “green toque,” according to my mother. The older Russians in the box were incensed. “How could Boris call it “green” and what was a “toque?” It missed the whole point of Tatiana’s appearance and what’s more, it was a disservice to Pushkin and Tchaikovsky. Going back stage after the performance, they chastised Boris for the “sin” of this translation.

The fact of the matter is that Boris was not the first translator who had had difficulty with this passage. Even those who do not have to contend with music find it troublesome. The great writer, Vladimir Nabokov, in his four-volume work about “Eugene Onegin” side-steps the dilemma of the raspberry-colored adjective by using a single French word “framboise” as in the following translation of Part 8, verse 17, lines 8-10:

“Tell me, Prince, you don’t know

who is it there in the framboise beret

talking with the Spanish ambassador?” [1]

I am uncertain what occurred after this event as Boris mulled over his translation and the reaction it engendered. What I suspect is that he must have had some second thoughts about his “green toque.” In the published version of his translation that appeared years later, the passage reads:

“But tell me, Prince, who is that girl

The one who wears with such distinction

The scarlet feather in her hat? [2]”

Would the Russians who were so upset in 1946 have been entirely satisfied with Boris’ new version? I doubt it. After all, there is no feather in Pushkin’s poem, the color scarlet does not have the subtlety of a raspberry hue, and by introducing a feather, the original head gear of a fashionable beret (in which a feather would be out of place) must be scrapped for an ordinary hat.

What I do know is that many opera companies, including the Metropolitan Opera in New York, appeared to have been satisfied with this solution, and so it stands to this day.

[1] Nabokov, Vladimir, Eugene Onegin, New York, Pantheon books, 1964 volume 1 (of 4), p. 299.

[2] “EUGENE ONEGIN: Lyrical Scenes in Three Acts, Text (after Pushkin) and Music by Peter Tchaikovsky, English version by Boris Goldovsky, New York, London: G. Schirmer, 1969.